Mike Wolanin | The Republic People vote in the midterm elections at NexusPark in Columbus, Ind., Tuesday, Nov. 8, 2022.

The percentage of Bartholomew County voters who cast straight-ticket votes for Tuesday’s midterm election was the highest in at least 16 years, reflecting a nationwide trend that researchers say is largely being fueled by the nationalization of local politics.

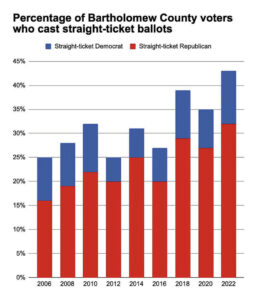

Nearly 43% of Bartholomew County voters who participated in Tuesday’s midterm marked the straight-ticket option on their ballots — the highest percentage since at least the 2006 midterm election, according to records from the Bartholomew County Clerk’s Office.

By comparison, straight-ticket voting accounted for an average of 28% of all votes cast in Bartholomew County in the six countywide elections held from 2006 to 2016, before jumping to 39% in the 2018 midterm and 35% in the 2020 presidential election.

A total of 32% of all ballots cast in Bartholomew County for Tuesday’s election — roughly 1 in 3 votes – were straight-party votes for the Republican ticket, double the percentage of straight-ticket GOP votes in the 2006 midterm.

At the same time, 11% of local voters voted straight-ticket Democrat, slightly higher than the 10% in the 2018 midterm and the highest percentage since at least 2006. Just four voters cast straight-ticket ballots for the Libertarian Party in Tuesday’s election.

Overall, 4,847 more people in Bartholomew County voted straight-ticket Republican than straight-ticket Democrat in Tuesday’s election.

Straight-ticket voting

Straight-ticket voting, also known as straight-party voting, allows voters to select a political party’s entire slate of candidates with the push of one button or the stroke of a pen.

Indiana was one of just six states that had an official straight-ticket option that voters could select on the ballot for this year’s midterm election, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. The other states were Alabama, Kentucky, Michigan, Oklahoma and South Carolina.

Voters in the rest of the country could still vote for a party’s entire docket of candidates but had to select them one by one as they went through the ballot.

Critics have said that having an option to vote straight-ticket encourages voters to be less informed, makes it easier for more extreme candidates to get elected and make it harder for third-party candidates to gain traction, according to the MIT Election Data and Science Lab. Proponents, however, say it saves times at the polls and reduces that chances the voters submit incomplete ballots.

The number of states offering the option has been on the decline. In 1994, 19 states had an official straight-ticket option, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Indiana does not allow straight-ticket voting in at-large races.

However, the option to vote straight ticket, which is becoming more popular in Bartholomew County, also was commonly used by voters in other counties in Indiana during the 2022 midterm — accounting for 69% of all votes cast in Marion County, 51% of all votes in Jackson County and 48% of votes in Allen County, according to records from each county.

In Democratic strongholds such as Marion and Monroe counties, straight-ticket Democrat votes far outnumbered straight-ticket Republican votes.

A convenient option

Bartholomew County Republican Party Chairwoman Luann Welmer said she is unsure why higher percentages of local voters are opting to cast straight-ticket votes but said GOP voters are “coming to the polls educated” and voting straight ticket can be easier.

“I do think it’s easier. I believe that most of our voters are coming to the polls educated, and they know who they want to vote for,“ Welmer said. “So, they’ve already made their decisions most of the time. …I feel like they wanted the Republican ticket, and that’s just what they chose.”

Former Bartholomew County Republican Party Chairwoman Barb Hackman attributed the larger percentage of straight-ticket Republican votes in Tuesday’s election, in large part, to the national political conversation, particularly Republicans’ focus on inflation and border security.

“What is happening nationally is what played a big part for Bartholomew County in what I would call a (local) red wave,” Hackman said. “…I think (voters) really pay more attention to national politics.”

Local Democrats have a different view, however.

Bartholomew County Democratic Party Chair Steve Schoettmer said the large gap between straight-ticket votes for the two parties reflects political tribalism among the local GOP. Schoettmer said he would like to see Indiana abolish the straight-party option.

“(Republicans) vote for the tribe. Democrats … vote for the person,” Schoettmer said “So when they show up, they just don’t hit that ‘D.’ They look at the name, they look at the people, they try to vote for who they believe to be the best candidate. On the Republican side, it’s more of a power play. It’s more of, ‘We want our team to call the shots.’”

Democrat Ross Thomas, who lost his bid to unseat Rep. Ryan Lauer, R-Columbus, in the 2022 midterm, expressed similar views as Schoettmer.

“Part of the Republican mentality is, ‘We’re on our team, and we’re going to vote for our team no matter what. …I don’t care if there’s a cardboard box on the ballot, he’s going to get my vote if he has an R by his name,’ ” Thomas said.

National trend

Researchers say the increase in straight-ticket voting in Bartholomew County reflects trends seen across the country as voters who identify with both parties react to negative partisanship and increasingly view local politics through the prism of national politics.

As a result, it has become increasingly difficult for individual candidates to separate themselves from their national party brand, said Steven Webster, an assistant professor of political science at Indiana University, who studies voting behavior, polarization and anger and politics.

“That is absolutely a trend that we see throughout the country with this over time increase in the proportion of voters who are voting consistently loyal for one party, so an increase in straight-ticket voting,” Webster said. “That is driven in large part by what political scientists call the nationalization of American politics. …What this means is that voters view their local candidates through the lens of national politics, and they care less about what individual represents them, and more about the party that represents them.”

At the same time, voters are increasingly being motivated by “negative partisanship,” meaning they are “not really voting for parties in candidates that they like,” but rather “against parties and candidates they don’t like,” Webster said.

“Increasingly … a voter who votes straight-ticket Democratic is saying, ‘I want to keep the Republican Party out of power,’ and the opposite is true with a straight-ticket Republican vote,” Webster said. “So what these straight-ticket votes mean isn’t always necessarily an affirmation or indication of support for a party, but rather an expression of dislike or fear of the other party.”

“I think it gives politicians a real incentive to appeal to anger into negativity,” Webster added. “Anger and negativity tend to push individuals off the sidelines and gets them to participate in politics. So, in one sense, it’s good because it boosts participation, and we generally think it’s good when Americans participate. But on the other hand, it sort of creates a nasty style of politics, a very confrontational style of politics, where really all I have to do is get you fearful of the other side, rather than give you a sort of positive or optimistic reason to vote for my side.”

Andy East | The Republic

Andy East | The Republic